Embracing AI in Legal Education

How universities are preparing law students for an AI-driven future

Artificial Intelligence has rapidly become a fixture in higher education, and university law schools are no exception. Across the UK, law faculty are grappling with how best to respond as their students turn to AI tools like ChatGPT for help with studies. Banning these tools outright is no longer the prevailing approach. Instead, universities are seeking ways to embrace AI responsibly, ensuring students use it ethically and effectively.

This report explores how university law departments are adapting to the AI age, how students are already using AI (with or without permission), the potential risks of unguided AI use, and how providing access to trusted legal AI solutions like Lexis+ AI can mitigate those risks and better prepare students for their future careers.

Law students are already using AI, with or without guidance

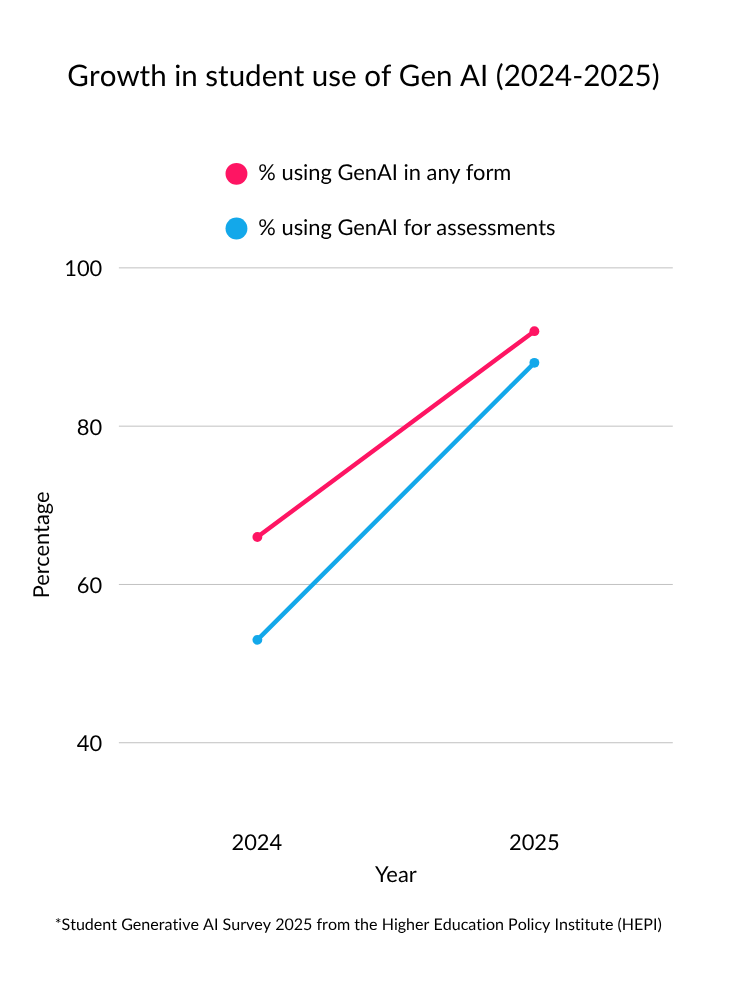

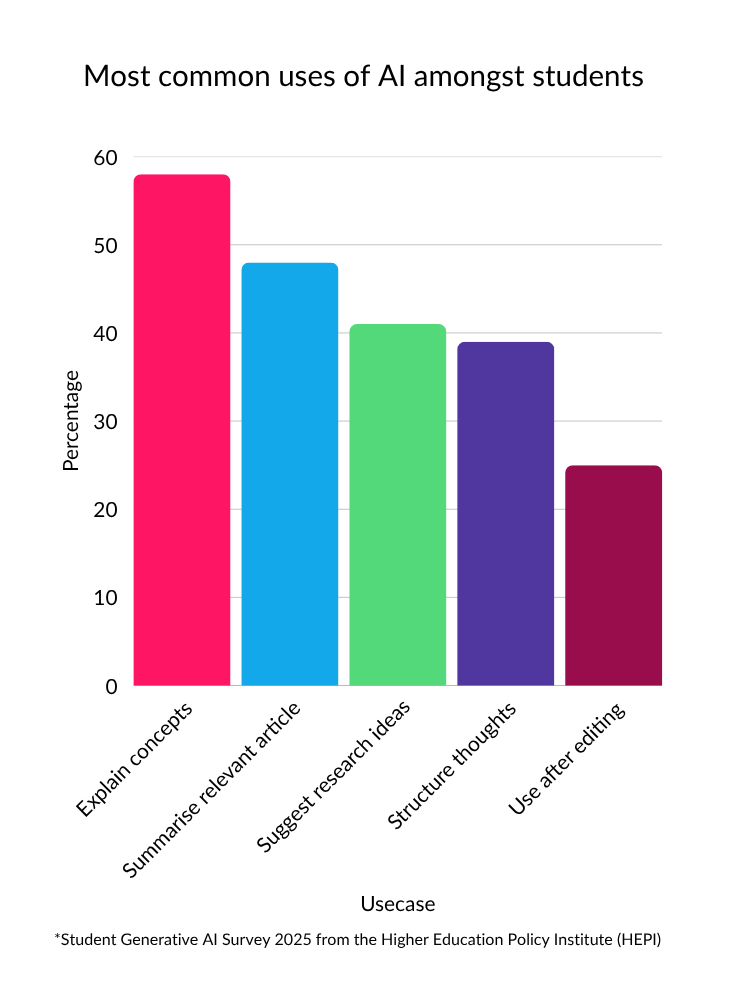

AI usage among students has surged dramatically. According to the Student Generative AI Survey 2025 from the Higher Education Policy Institute (HEPI), 92% of students are now using AI tools in some form, up from 66% the year before. In fact, 88% of students report using generative AI for their coursework or assessments. Common uses include prompting AI to explain complex legal concepts, summarising journal articles, or requesting research ideas. Clearly, today’s law students see AI as a valuable study aid that can save time and even improve the quality of their work.

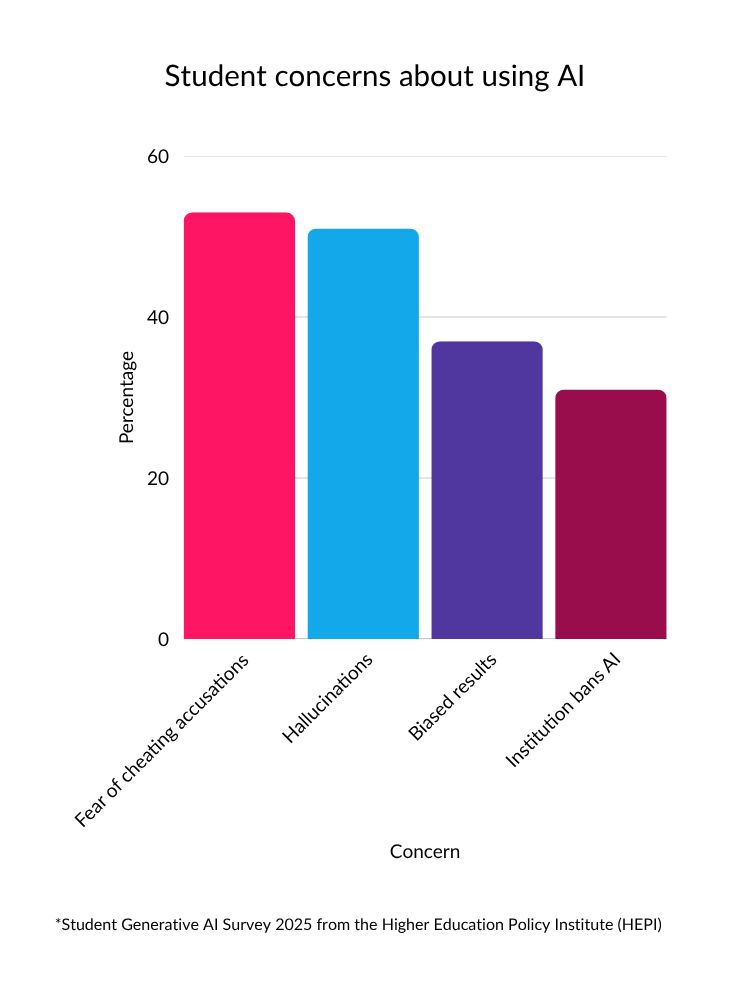

However, this widespread use of AI is often happening ahead of official university policies or formal training. Many students are experimenting on their own, unsure where the boundaries lie. “We’ve got to find a middle ground,” said one UK law student at a roundtable discussion organised by the Law Society’s Leadership and Management Section in February 2024. She noted that she comfortably uses ChatGPT to summarise information and aid her understanding of legal materials but is hesitant to use it for writing actual coursework without guidance. “No one is telling us what we can do,” she explained. This sentiment is echoed by students nationwide who are calling for clearer guidelines. They know AI is here to stay, but don’t want to run afoul of rules or undermine their own learning.

Universities have begun to respond. By July 2023, all 24 Russell Group universities had reviewed their academic conduct policies in light of generative AI. Initial talk of outright bans on tools like ChatGPT has given way to a recognition that “students should be taught to use AI appropriately in their studies, while also [be made] aware of the risks of plagiarism, bias and inaccuracy in generative AI.”

These universities agreed on guiding principles to support students and staff to become “AI literate” and to adapt teaching and assessment for the ethical use of AI. In short, the consensus is that AI literacy is now an essential skill for law students, one to be encouraged, not penalised, as long as it is used transparently and responsibly.

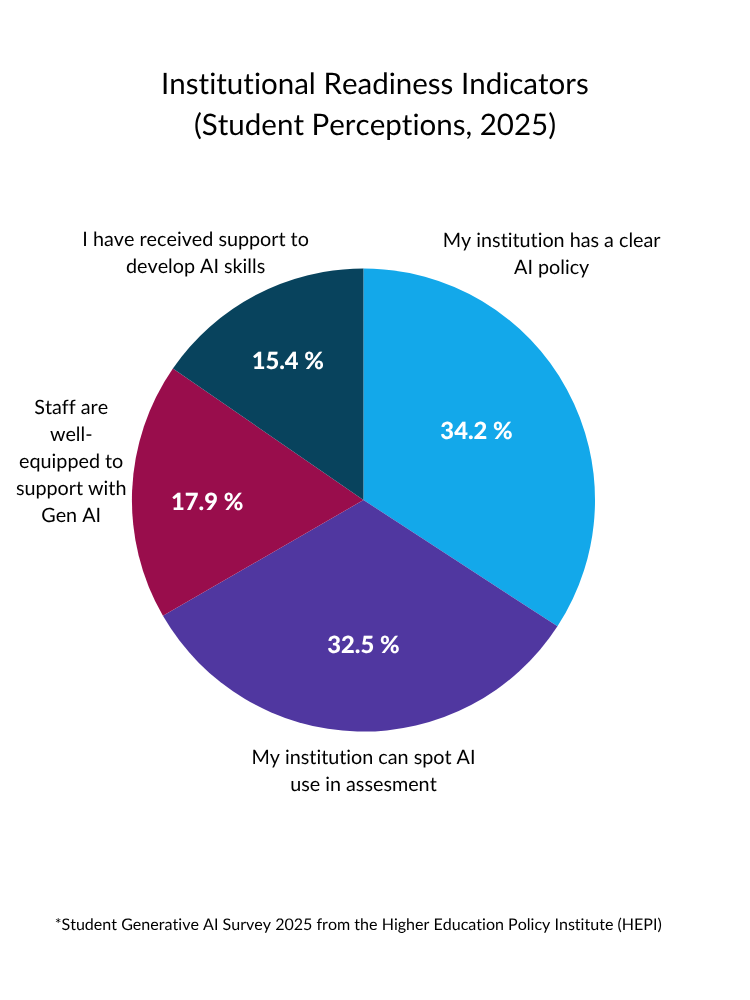

Yet a gap remains between policy and practice. According to HEPI, 80% of students say their institution now has a clear AI policy and a majority believe universities would detect AI misuse, but only 36% have received any support or training from their institution on how to use AI tools effectively. Students overwhelmingly feel that having good AI skills is “essential” for their future, but many are essentially self-teaching these skills. This highlights a key challenge for law faculties: how to equip students with AI skills and guardrails, so they can reap the benefits of AI without undermining academic integrity or their own learning process.

The risks of unsupervised AI use in legal studies

Allowing students to use AI without guidance carries certain risks, particularly in the context of legal education where accuracy and sound reasoning are paramount. Perhaps the biggest concern is the risk of hallucinations: false or fabricated information generated by AI that looks credible. Generative AI tools can produce answers that sound highly confident and authoritative yet are completely wrong. As Dame Victoria Sharp, president of the King’s bench division of the high court, warned in a recent ruling: AI tools “can produce apparently coherent and plausible responses […] but those responses may turn out to be entirely incorrect. […] They may cite sources that do not exist. They may purport to quote passages from a genuine source that do not appear in that source.” In other words, an AI platform like ChatGPT might invent a legal case or a bogus statute citation in its answer and a student without strong research skills might not realise it before using it.

This is not a theoretical worry; it’s already happened in practice. In 2025, in the case of Al-Haroun -v- Qatar National Bank, the high court was confronted with 45 case-law citations, 18 of which were false. This was apparently the result of both claimant and solicitor relying on AI tools without verification. In the case of Frederick Ayinde -v- The London Borough of Haringey, Haringey Law Centre’s cited phantom case law that opposing counsel couldn’t locate, leading to embarrassment and sanctions. These incidents prompted the urgent guidance from Dame Victoria Sharp, who warned the profession about the “serious implications for the administration of justice and public confidence in the justice system if artificial intelligence is misused. ” The judgment of the Divisional Court went so far as to warn that lawyers who submit AI-fabricated materials could face contempt of court or worse. For law students, the lesson is clear: relying on generative AI blindly can lead to trusting law that isn’t real, a mistake with potentially severe academic or professional consequences. As Gabriella Yuin-Li Rasiah, one of our former student ambassadors, now a trainee solicitor at DWF Law LLP, put it:

“One of the key pieces of advice I’d offer students is to embrace technology as a tool to enhance efficiency and precision in their work, but not to place blind reliance on it. For example, an AI tool may be able to produce an email response, but the individual who presses ‘send’ is accountable for any mistakes in the email. Make sure to proofread your work.”

Another risk is that overreliance on AI could stunt the development of essential legal research and reasoning skills. If a student prompts an AI tool to produce an essay or solve a legal problem from start to finish, they may get the answer but miss out on the critical thinking process. If AI writes that essay, is it a student’s answer? Or AI’s? That concern was voiced by the law student mentioned earlier, as well as by educators. “There’s a danger of losing my independence,” the student reflected, worrying that heavy use of AI might short-circuit her ability to form her own legal arguments.

Law professors similarly note that students must still learn to think critically about AI outputs. Nowadays, “developing a critical skill set will be a core of legal education,” Luke Corcoran, senior lawyer at the Government Legal Department, agreed in the LawGazette, noting that whether information comes from “a human client or a machine, lawyers need to be able to say ‘does this pass the smell test?" In other words, analytical scepticism and fact-checking are more important than ever when AI is in the mix. Without guidance, students may not know they need to double-check AI results against primary sources or how to prompt the AI effectively to get useful (and truthful) outputs.

Finally, universities remain concerned about academic integrity. Generative AI makes it easier for students to produce work that isn’t entirely their own, raising questions of plagiarism or cheating. The Russell Group guidelines are written to ensure that “academic integrity is upheld” and that students acknowledge their use of AI where appropriate. If students try to secretly use AI tools such as ChatGPT write an essay in its entirety, they not only risk disciplinary action, but also cheating themselves out of learning. Thus, the push toward including AI is anchored in transparency and ethical use, incorporating AI into learning in permissible ways (for example, to brainstorm or outline ideas, which many view as acceptable), while forbidding its use in place of the student’s own analysis in graded work, unless disclosed.

It’s a delicate balance, and one that is still evolving. As Patrick Grant, project director for legal tech and innovation at the University of Law said, “the entire profession ‘needs a massive education programme’ on the capabilities and risks of generative AI.” In short, the solution is not to abandon AI, but to teach the next generation of lawyers how to use it properly.

From caution to curriculum: how law universities are adapting

Recognising these challenges, many law faculties in the UK are creating proactive strategies to integrate AI into their curriculums. The era of quietly ignoring students' use of AI (or issuing blanket bans) is ending. Instead, schools are beginning to train students and staff in the savvy use of AI. The Russell Group has provided a roadmap – Russell Group principles on the use of generative AI tools in education – across five principles, committing universities to:

1. AI literacy for all

Support students and lecturers in becoming competent with AI tools, ensuring everyone has a baseline understanding of how generative AI works and its appropriate uses. And that includes AI’s limitations.

2. Training educators

Equip academic staff to guide students on using AI appropriately in their studies. Faculty need development too, so they can incorporate AI into teaching and help students navigate it responsibly.

3. Adapt teaching and assessment

Redesign learning activities and exams to integrate the ethical use of AI. This might include assignments that allow or even require AI use (with proper attribution), as well as new forms of assessment that minimise opportunities for AI-enabled cheating and instead test deeper skills.

4. Upholding integrity

Update academic conduct policies so it’s clear where AI use is permitted vs. inappropriate. Students should know, for example, whether they must declare AI assistance on an essay or if submitting AI-generated work as their own is unacceptable.

5. Sharing best practices

As this technology evolves, universities will collaborate and share what works (and what doesn’t) in teaching with AI, creating a community of practice to keep policies and teaching methods up to date.

Crucially, the ethos is to make best use of AI and its advantages whilst mitigating its risk and protecting the quality of academia that Russell Group universities are known for. Law schools are taking these principles to heart and formalising AI training.

In the US, a LexisNexis survey found that 78% of law faculty planned to teach students about generative AI tools. We're seeing similar momentum in the UK. Workshops on prompt engineering (crafting effective questions for AI) and on detecting AI-generated text are becoming more common. The goal is to ensure that by graduation law students are not just AI users but responsible, informed AI users: comfortable leveraging the technology, aware of its pitfalls, and skilled in checking its outputs against authoritative sources.

Mitigating the risks: why law students can rely on Lexis+ AI for accurate, ethical research

Universities can harness the benefits of AI while managing its risks by providing access to vetted, purpose-built legal AI tools. This is where Lexis+ AI comes in. Unlike open AI that draws on the internet and potentially false sources, Lexis+ AI is built and trained on LexisNexis’s vast, authoritative legal database, the largest repository of legal content in the UK. As a result, when Lexis+ AI answers a legal question, its responses are grounded in verified case law, legislation and provides cited references to back up its answers.

This dramatically lowers the risk of hallucinations; it's showing you exactly where it found the answer. Students using Lexis+ AI can therefore develop their research skills in tandem with AI, learning to trace every assertion to a reliable source rather than taking an AI response at face value.

In public AI chatbots, any question you ask could be stored or even used to further train the model, raising confidentiality issues. In contrast, Lexis+ AI was built with privacy by design and guided by the Responsible Artificial Intelligence Principles at RELX. A law student using Lexis+ AI through their university is operating in a secure environment; their queries and documents remain private. This makes Lexis+ AI safe for academic research (or even law clinic work) where sensitive facts might need to be discussed. Students and faculty can experiment freely with Lexis+ AI on real legal problems without fear that data is leaking or being improperly used.

For law faculty concerned that AI might discourage students from honing traditional skills, Lexis+ AI offers a reassuring solution. Because it is integrated with the Lexis legal research ecosystem, it encourages proper research methodology. A student might ask Lexis+ AI to draft a quick memo on a contract law issue or summarise the key points of a case, but the output comes with citations and links into deeper research tools. The student can seamlessly transition from the AI’s summary to reading full case judgments, statutes, or commentary in Lexis+. In this way, AI becomes a bridge – not a shortcut – to deeper learning.

Embracing the tools of the future

The message for students at UK universities and their professors is clear: AI is here to stay and students are already engaging with it. The question is whether we help them use it wisely or leave them to navigate it alone. The experiences of universities so far show that the best approach lies in integration, not prohibition. By embracing AI in the law curriculum – through clear guidelines, skills training, and the provision of safe, authoritative tools like Lexis+ AI – educators can turn a potential challenge into a powerful opportunity. Students can gain the advantages of AI while avoiding the pitfalls of misinformation and misuse.

Ultimately, adopting Lexis+ AI for students isn’t just about avoiding the negatives; it’s about actively preparing the next generation of lawyers for the world they will enter. Today’s law students will practice in an AI-enhanced legal profession, one where the ability to collaborate with AI will be a hallmark of the most successful practitioners.

Law faculty have a pivotal role to play in readying students for this reality. By teaching students how to use the tools of the legal profession ethically and effectively you will ensure that they won’t merely adapt to their future but help lead and shape it. In the end, an AI-ready law graduate will be one who can deliver better results for clients, uphold higher standards of accuracy and justice, and continue the proud tradition of legal excellence in the UK, augmented by the best that technology has to offer.

Sources

- High court tells UK lawyers to stop misuse of AI after fake case law citations, The Guardian, June 2025.

- Ayinde -v- London Borough of Haringey and Al-Haroun -v- Qatar National Bank Approved Judgment, June 2025.

- Student Generative AI Survey 2025, The Higher Education Policy Institute (HEPI), February 2025.

- King's partners with Linklaters to launch GenAI Expert Training Programme, King’s College London, October 2024.

- Linklaters Launches GenAI Expert Training Programme, Linklaters.com, October 2024.

- Lexis+ AI Insider Hub, LexisNexis.co.uk (UK).

- How Lexis+ AI Delivers Linked Legal Citations, LexisNexis.co.uk (UK).sponsible Artificial Intelligence Principles at RELX, RELX.com.

- News focus: Generative AI - law students call for guidance, Law Gazette, February 2024.

- LexisNexis Rolls Out Free Access To Lexis+ AI For Law Students, LexisNexis.com (US), January 2024.

- UK universities draw up guiding principles on generative AI, The Guardian, July 2023

- Russell Group principles on the use of generative AI tools in education, Russell Group, July 2023.